Yersinia bacteria: can it be eliminated in the intestine?

Posted: 30 March 2023 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

This article outlines new research from the University of Pennsylvania, concerning Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a relative of the bacterial pathogen that causes plague by triggering the body’s immune system to form lesions in the intestines.

Yersinia bacteria

Yersinia bacteria cause a variety of human and animal diseases, the most notorious being the plague, caused by Yersinia pestis. The plague pathogen is blood-borne and transmitted by infected fleas.

A relative, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, causes gastrointestinal illness and is less deadly but naturally infects both mice and humans, making it a useful model for studying its interactions with the immune system.

These two pathogens have many traits in common, particularly their knack for interfering with the immune system’s ability to respond to infection. Infection for these two depends on ingestion. Yet the focus of much of the work in the field had been on interactions of Yersinia with lymphoid tissues, rather than the intestine.

Biomarkers aren’t just supporting drug discovery – they’re driving it

FREE market report

From smarter trials to faster insights, this report unpacks the science, strategy and real-world impact behind the next generation of precision therapies.

What you’ll unlock:

- How biomarkers are guiding dose selection and early efficacy decisions in complex trials

- Why multi-omics, liquid biopsy and digital tools are redefining the discovery process

- What makes lab data regulatory-ready and why alignment matters from day one

Explore how biomarkers are shaping early drug development

Access the full report – it’s free!

A new study of Y. pseudotuberculosis, led by a team from University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine, US, demonstrated that, in response to infection, the host immune system forms small, walled-off lesions in the intestines called granulomas.

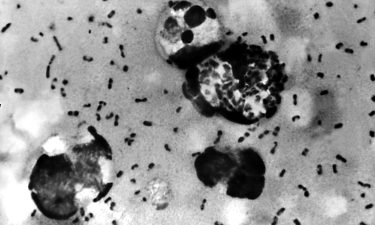

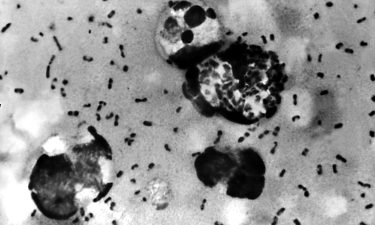

Y. pseudotuberculosis bacteria which caused Bubonic Plague. 1965

This is the first time these organised collections of immune cells have been found in the intestines in response to Yersinia infections. The team went on to show that monocytes sustain these granulomas. Without them, the granulomas deteriorated, allowing the mice to be overtaken by Yersinia.

The findings, published in Nature Microbiology, have implications for developing new therapies that leverage the host immune system. A drug that harnessed the power of immune cells to not only keep Yersinia in check but to overcome its defences, it could potentially eliminate the pathogen altogether.

“Our data reveals a previously unappreciated site where Yersinia can colonise and the immune system is engaged,” said Professor Igor Brodsky, senior author on the work. “These granulomas form in order to control the bacterial infection in the intestines. We show that if they do not form or fail to be maintained, the bacteria are able to overcome the control of the immune system and cause greater systemic infection.”

Three Yersinia infections

The three Yersinia infections: Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica share a keen ability to evade immune detection. Y. enterocolitica affects swine and can cause food-borne illness if people consume infected meat.

The discoveries also point to the intestines as a key site of engagement between the immune system and Yersinia.

“In all three infections, a hallmark is that they colonise lymphoid tissues and are able to escape immune control and replicate, cause disease, and spread,” Brodsky explained.

Earlier studies had shown that Yersinia prompted the formation of granulomas in the lymph nodes and spleen but had never been observed in the intestines, until Brodsky’s team took a closer look at the intestines of mice infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis.

Y. pseudotuberculosis is an orally acquired pathogen, thus the researchers were interested in how the bacteria behaved in the intestines. The initial observation following Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection, was macroscopically visible lesions all along the length of the gut that had never been described before. These same lesions were present when mice were infected with Y. enterocolitica, forming within five days after an infection.

A biopsy of the intestinal tissues confirmed that the lesions were a type of granuloma, known as a pyogranuloma, composed of a variety of immune cells, including monocytes and neutrophils.

Granulomas form in other diseases that involve chronic infection, including tuberculosis. Somewhat paradoxically, these granulomas — while key in controlling infection by walling off the infectious agent — also sustain a population of the pathogen within those walls.

The team wanted to understand how these granulomas were both formed and maintained, working with mice lacking monocytes as well as animals treated with an antibody that depletes monocytes. In the animals lacking monocytes “these granulomas, with their distinct architecture, would not form,” Brodsky described.

Instead, a more disorganised and necrotic abscess developed, neutrophils failed to be activated, and the mice were less able to control the invading bacteria. These animals experienced higher levels of bacteria in their intestines and succumbed to their infections.

Groundwork for the future

The researchers believe the monocytes are responsible for recruiting neutrophils to the site of infection and thus launching the formation of the granuloma, helping to control the bacteria. This leading role for monocytes may exist beyond the intestines, the researchers believe.

“We hypothesise that it’s a general role for the monocytes in other tissues as well,” said Brodsky.

The discoveries also point to the intestines as a key site of engagement between the immune system and Yersinia.

Peyer’s patches are small areas of lymphoid tissue present in the intestines that serve to regulate the microbiome and fend off infection. “Previous to this study we knew of Peyer’s patches to be the primary site where the body interacts with the outside environment through the mucosal tissue of the intestines,” added Brodsky.

In future work, Brodsky and colleagues hope to continue to piece together the mechanism by which monocytes and neutrophils contain the bacteria.

A deeper understanding of the molecular pathways that regulate this immune response could one day offer inroads into host-directed immune therapies, by which a drug could tip the scales in favour of the host immune system, unleashing its might to fully eradicate the bacteria rather than simply corralling them in granulomas.

Related topics

Antibodies, Bacteriophages, Immunology

Related conditions

bacterial infections, Plague

Related organisations

University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine

Related people

Professor Igor Brodsky