A new genetic biomarker to predict immunotherapy success

Posted: 16 February 2024 | Ellen Capon (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Tumours with a greater IGR burden could respond better to immune checkpoint blockades, advancing precise treatments for patients.

Scientists at the University of Pittsburgh have discovered that tumours with a greater intragenic rearrangement (IGR) burden may respond better to immune checkpoint blockades (ICB). This could lead to more precise treatment for patients with cancers like oesophageal, breast, ovarian and endometrial, which solves an unmet need to discover genetic abnormalities that predict ICB responses in these tumour types.

Tumour mutational burden

Immunotherapy can cause severe immune-related side effects and can even accelerate cancer progression in some patients. Cancer immunotherapies have a unique toxicity profile dependent on their mechanism of action, related to upregulation of immune activity, which can lead to life threatening organ toxicity.1

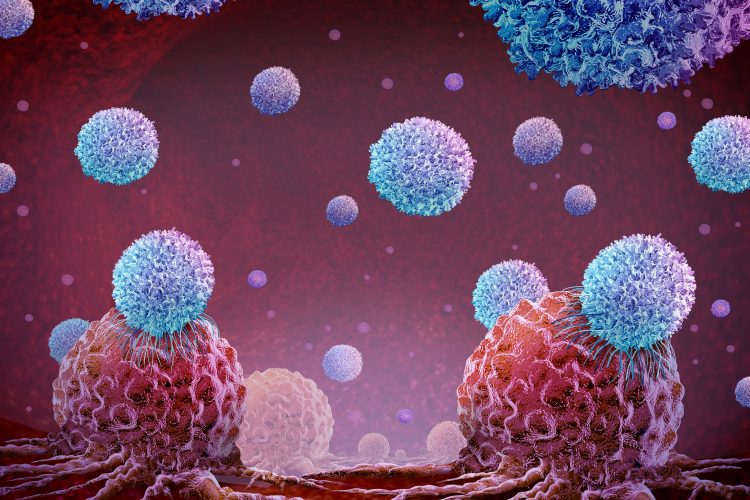

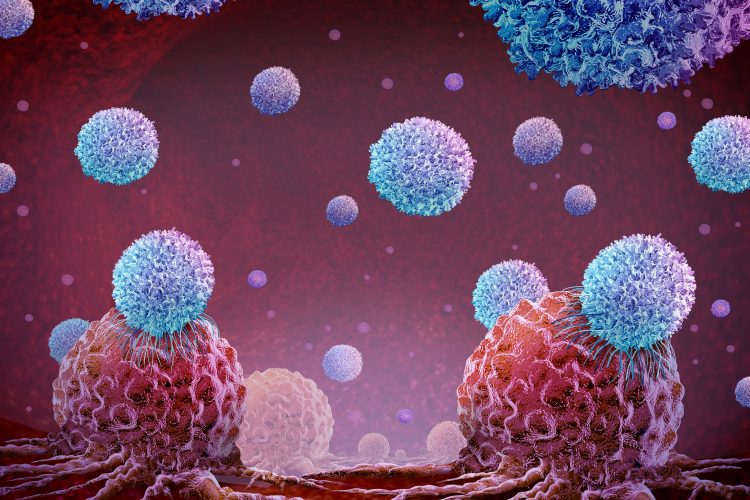

Therefore, it is essential to correctly identify the patients that are likely to respond. One method is to study the tumour mutational burden (TMB). TMB is an emerging biomarker defined as the total number of mutations per coding area of tumour genome.2 Cancerous cells are derived from healthy cells in the body, meaning that they frequently are undetected by the immune system, but when cancers have a high TMB, T cells can better recognise and destroy the malignant cells. A patient is a good candidate for immunotherapy if their tumour has a high TMB.

However, Dr Xiaosong (Jonathan) Wang, senior author of the paper and associate professor of Pathology at Pitt and UMPC Hillman Cancer Center, explained: “Genetic tests are available that are great at predicting immunotherapy response in melanoma and lung cancer, but they don’t work well in some other cancers. To help fill this gap, we developed a new approach, which analyses a class of hidden, or cryptic, rearrangements in the cancer genome.”

Dr Wang and his team utilised a database from the International Cancer Genomic Consortium to analyse over 1,000 cancer genomes across a variety of cancer types. For the first time, the researchers demonstrated that measuring the overall burden of IGR could potentially predict immune cell infiltration and immunotherapy response in certain cancers.

IGR results from structural rearrangements of a cell’s genome. Dr Wang commented: “TMB, which measures simple mutations has been intensively studied, whereas IGR represents the dark side of cancer genetics because these aberrations are cryptic and difficult to study.”

Two distinct classes of cancers

The researchers investigated the relationship between IGR and TMB in different tumour types. In cancers with high TMB, like melanoma and lung cancer, there was a low IGR burden. Contrastingly, oesophageal, breast, ovarian and endometrial cancers had a low TMB but high IGR burden.

Also, a correlation between high IGR burden or high TMB with elevated T cell inflammation was observed: elevated levels of either of these genetic abnormalities enabled immune cells to better recognise cancers. Dr Wang elucidated: “Our findings point to the existence of two distinct classes of cancers: those driven by simple mutations, or TMB-dominant, and those driven by intragenic rearrangements, or IGR-dominant.”

He continued: “This suggested to us that patients who don’t qualify for immunotherapy because of low TMB might still benefit from the treatments if they have a high IGR burden.”

Examining clinical trial datasets

The researchers studied several clinical trial datasets to test their hypothesis that high IGR burden is associated with immunotherapy response in IGR-dominant cancer. In the dataset of patients with oesophageal cancer who were treated with the immunotherapy drug durvalumab, the individuals with a higher IGR burden responded better. Most of those with disease relapse had a lower IGR burden.

Unexpectedly, in a dataset of bladder cancer patients treated with the immunotherapy drug atezolizumab, the team saw that because bladder cancer is a TMB-dominant cancer type, TMB predicted response and survival. However, the patients that had been exposed to platinum-based chemotherapy before atezolizumab had a greater IGR burden. This may be explained by the damage of DNA which induces structural rearrangements of the genome following platinum exposure.

These results demonstrate how IGR test findings could be used by clinicians in different cancer types to decide on the best treatment. Furthermore, the cost of the whole genome sequencing has reduced, meaning that measuring IGR burden may be soon affordable and feasible. Now, the team are developing and standardising their test and algorithm further for clinical use.

This study was published in Cancer Immunology Research.

References

1 Mahalingam P, Newsom-Davis T. Cancer immunotherapy and the management of side effects. Clinical Medicine Journal. [Internet] 2023 January 25 [2024 February 14]; 23(1):56-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2022-0589

2 Calabuig-Farinas S, Garcia SG, Herrero CC, et al. Clinical and technical insights of tumour mutational burden in non-small cell lung cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. [Internet] 2023 February [2024 February 15]; 182. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103891

Related topics

Cancer research, Immunotherapy, Precision Medicine

Related conditions

Breast cancer, Cancer Research, Endometrial cancer, Oesophageal cancer, Ovarian cancer

Related organisations

University of Pittsburgh

Related people

Dr Xiaosong Wang (Pitt)