How MMR-deficient colorectal cancers regulate their growth

Posted: 9 July 2024 | Ellen Capon (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Understanding how MMR-deficient colorectal cancers drive tumour growth and avoid immune detection could pave the way for personalised cancer medicine.

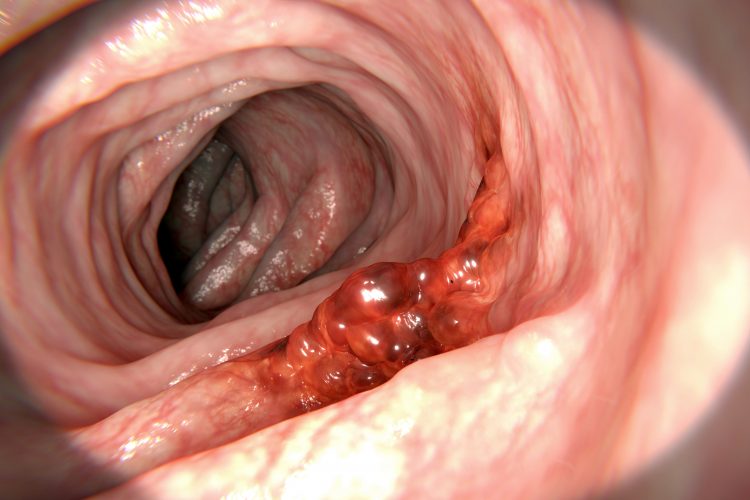

For the first time, scientists at UCL and University Medical Center Utrecht have observed bowel cancer cells’ ability to regulate their growth using a genetic on-off switch to increase their likelihood of survival. These results could pave the way for personalised cancer medicine, determining how aggressive a patient’s cancer is, and selecting the most effective therapeutics.

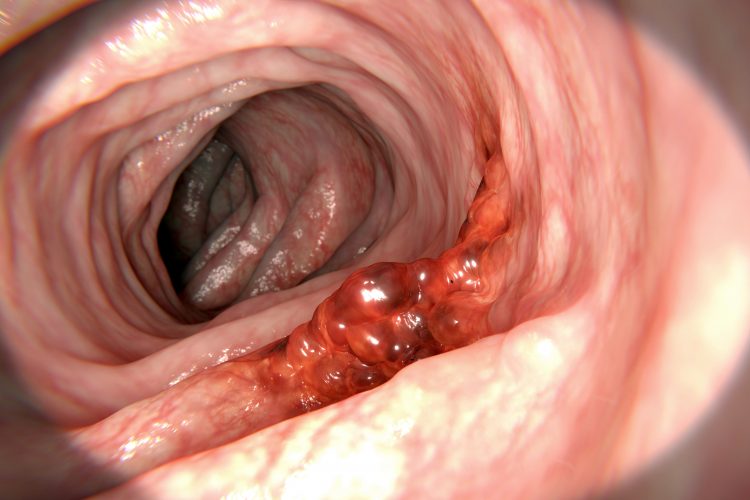

Bowel cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the UK, accounting for 11 percent of all new cancer cases from 2017 to 20191, and is the second most common cause of cancer death in the UK, accounting for 10 percent of all cancer deaths in the same time period.2

DNA repair mechanism disruption is a significant cause of increased cancer risk, with around 20 percent of bowel cancers known as mismatch repair deficient (MMRd) cancers, which have mutations in DNA repair genes. However, tumours do not always benefit from disrupting repair mechanisms, as each mutation heightens the risk of initiating the immune system to attack the tumour due to it being so altered from a normal cell.

Senior author of the study Dr Marnix Jansen, UCL Cancer Institute and UCLH, commented: “We predicted that understanding how tumours exploit faulty DNA repair to drive tumour growth – whilst simultaneously avoiding immune detection – might help explain why the immune system sometimes fails to control cancer development.”

Whole genome sequencing

The UCL team analysed whole genome sequences from 217 MMRd bowel cancer samples in the 100,000 Genomes Projects database, searching for associations between the total number of mutations and genetic changes in key DNA repair genes. A strong correlation between DNA repair mutations in the MSH3 and MSH6 genes was found, as well as an overall high volume of mutations. The researchers hypothesised that these mutations in DNA repair genes might control cancer mutation rates, which was validated in organoids grown from patient tumour samples.

Dr Suzanne van der Horst from University Medical Center Utrecht highlighted that the DNA repair mutations in the MSH3 and MSH6 genes act as a genetic switch that cancers exploit, explaining: “On one hand, these tumours roll the dice by turning off DNA repair to escape the body’s defence mechanisms. While this unrestrained mutation rate kills many cancer cells, it also produces a few ‘winners’ that fuel tumour development.”

She continued: “The really interesting finding from our research is what happens afterwards. It seems the cancer turns the DNA repair switch back on to protect the parts of the genome that they too need to survive and to avoid attracting the attention of the immune system. This is the first time that we’ve seen a mutation that can be created and repaired over and over again, adding it or deleting it from the cancer’s genetic code as required.”

First author Dr Hamzeh Kayhanian, UCL Cancer Institute and UCLH, added: “Like cancer cells, bacteria have evolved genetic switches which increase mutational fuel when rapid evolution is key, for example when confronted with antibiotics. Our work thus further emphasises similarities between evolution of ancient bacteria and human tumour cells, a major area of active cancer research.”

A patient may need more intense treatment if DNA repair has been switched off, providing the tumour with an opportunity to adapt quickly to avoid treatments, especially immunotherapies, which are designed to target heavily mutated tumours. Several cancers, like melanoma, urothelial bladder cancer and non-small lung cancer, can be treated with checkpoint blocking antibodies. In tumours with high mutation burden, caused by chronic exposure to DNA-damaging agents or DNA repair defects, immune checkpoint blockade has demonstrated most effectiveness.3

Bowel Research UK, Cancer Research UK and the Rosetrees Trust funded this research with grants. Georgia Sturt, Research and Grants Manager at Bowel Research UK concluded: “Bowel Research UK are delighted that our fundings has contributed to producing this exciting new data, and we look forward to seeing how these discoveries could change treatments for future patients.”

To discover the impact of cancer treatment on these DNA repair switches, the researchers have already begun a follow-up study.

This study was published in Nature Genetics.

References

1 Bowel cancer statistics. Cancer Research UK. [cited 2024 July 5] Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-Zero

2 Bowel cancer statistics. Cancer Research UK. [cited 2024 July 5] Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-One

3 Bulk, J, Miranda N, Verdegaal E. Cancer immunotherapy: broadening the scope of targetable tumours. Open Biology. 2018 June 6 [cited 2024 July 8]; 8. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsob.180037#d1e434

Related topics

Cancer research, DNA, Drug Targets, Genomics, Immunotherapy, Oncology, Organoids, Personalised Medicine, Sequencing

Related conditions

Cancer Research, Colorectal cancer

Related organisations

Bowel Research UK, Cancer Research UK, Rosetrees Trust, UCL, University Medical Center Utrecht