Blocking trogocytosis improves ability of CAR T-cell therapy to treat cancer in mice

Posted: 12 September 2022 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have found how tumours can avoid the immune system and cancer immunotherapies, including CAR T-cell therapies.

In a new study, researchers at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, US have uncovered a detailed mechanism by which tumours can skirt both the immune system and cancer therapies that leverage its power, such as genetically engineered CAR T-cell therapy.

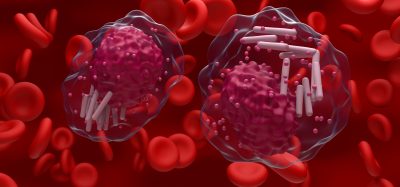

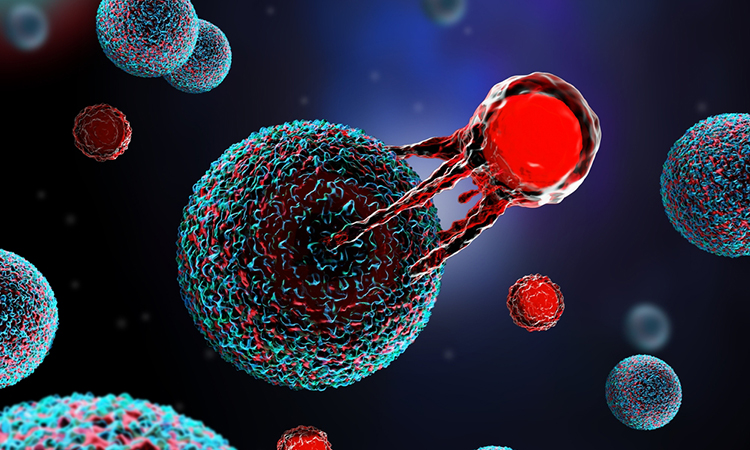

Their investigation, published in the journal Cell Metabolism, revealed how tumour-derived factors stimulate trogocytosis, a process where T cells interact with cancer cells and sometimes “nibble” a piece of the cancer cell membrane. When that membrane segment includes an antigen, a molecule specific to the cancer, the T cells may then begin expressing that antigen on their own cell surface, making it appear to other T cells like a cancer cell. Trogocytosis can affect a patient’s own T cells and those modified to become CAR T cells.

“Trogocytosis can lead to three different things and all three are bad for a person with a tumour,” said Serge Fuchs, the senior author on the work. “First of all, the tumour cell did not get killed and has lost an antigen, which may mean that even if another, better equipped T cell comes along, it will not recognise it, giving cancer cells a window of opportunity to grow unchecked. The second problem is, for reasons we still do not understand, once a T cell takes a piece of the tumour cell membrane, it becomes much less active. The third problem is very ironic, because now, a T cell that displays tumour antigen, this ‘sheep in wolf’s clothing,’ may then become victim to ‘fratricide’, killed by another T cell.”

Overall, the result is a decline in killer T cell numbers and activity and a bump in opportunities for the cancer cells to escape detection and grow.

“What we see is that only a small number of cells undergo trogocytosis and then they disappear quickly because they are killed. So we are studying a vanishing act. It is hard to do – very expensive and very tedious – but it appears to be very important,” said Fuchs.

The researchers investigated tumour-derived factors, or the concoction of proteins, lipids and other materials that cancer cells secrete into the body. The team found that collecting these secretions and exposing the resulting solution to T cells hampered the cells’ ability to do their cancer-fighting job.

“Just exposing them to this tumour-conditioned media caused them to kill fewer cancer cells, trogocytose more and get killed more,” Fuchs said.

Trogocytosis was previously believed to have something to do with cancer’s ability to hinder anti-cancer immunity, but the team pinned down the mechanism, showing that T cells exposed to tumour-derived factors experienced a notable decline in levels of the gene CH25H. This gene is known to be involved in altering cell’s lipid membranes and can inhibit two cell membranes from fusing together – an essential process for trogocytosis to occur. When they added back a metabolite produced by CH25H, they could block trogocytosis.

Further characterisation of the pathway helped the team identify another player, the gene ATF3, which opposes the activity of CH25H. Eliminating AFT3 prevented trogocytosis from occurring and restored the ability of T cells to kill tumour cells.

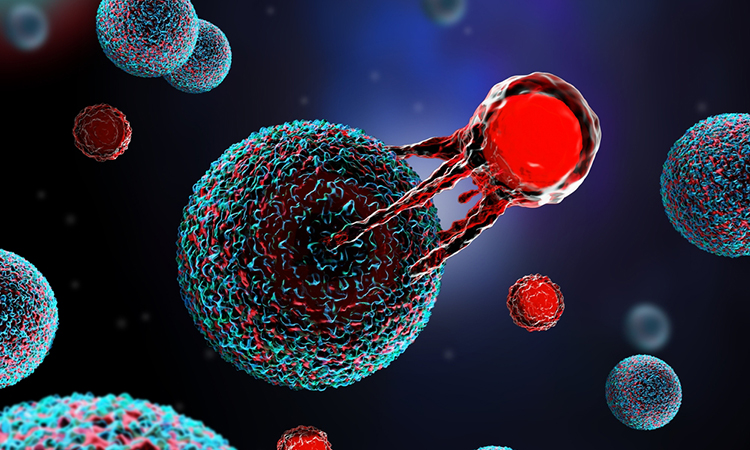

Not only do the new insights suggest novel targets for anti-cancer therapies, but they may have immediate significance for CAR T-cell therapy. Since trogocytosis could impair the effectiveness of the engineered T cells delivered in CAR T cells, the researchers surmised that blocking this could improve CAR T-cell performance.

“We figured, why not use what is cleverly known as an ‘armoured CAR’ approach and co-express CH25H in the CAR T cells,” Fuchs said. “This turned out to be more efficient than the old CAR T cells.”

Indeed, delivering the CAR T cells adorned with CH25H improved the survival of mice with cancer compared to the unarmoured CAR T cells.

Though only a small percentage of T cells are involved in trogocytosis, it may be an underappreciated process when it comes to cancer immunity. With future work, the researchers intend to explore the roles of ATF3 and CH25H and other molecules in trogocytosis.

Related topics

Cell Therapy, Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs), Drug Targets, Immuno-oncology, Immunotherapy, T cells

Related conditions

Cancer

Related organisations

Pennsylvania University

Related people

Serge Fuchs