DNA barcoding reveals cancer cells’ ability to evade the immune system

Posted: 7 November 2022 | Ria Kakkad (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Using DNA barcoding to track cancer cells through time, scientists have shown that the cells have diverse abilities to escape the immune system.

Some cancer cells can deploy parallel mechanisms to evade the immune system’s defences as well as resist immunotherapy treatment, according to a new study from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Australia. The researchers used a technique called DNA barcoding, which tags cells with a known sequence and tracks the progression of tumour cells through time.

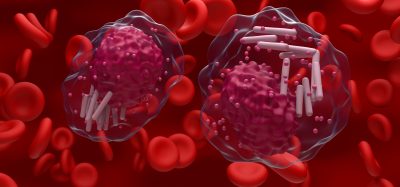

By suppressing the action of killer T cells and hindering the ability of the immune system to flag tumour cells for destruction, breast cancer cells are able to replicate and metastasise, according to a new study recently published in Nature Communications.

The mechanisms could be used as potential targets for therapies, to stop tumorous cells from adapting and spreading. Another future application could be in prognosis, where a high number of cells could indicate which patients might not respond to immunotherapy.

While immunotherapy is an effective treatment in many cancers, in some people their cancer cells evolve to outplay the immune system defences. This process is known as immunoediting, where interaction between tumour cells and immune cells results in many cancerous cells being destroyed by the immune system, but leaving some undetected, which continue to grow and spread.

The researchers used mouse breast cancer cells tagged with a known DNA ‘barcode’, a sequence that was passed on from one generation of cells to the next.

The DNA barcoding allowed the team to see where more aggressive, resistant cells came from, as they could trace it back to the original cell to see if it had grown or shrunk.

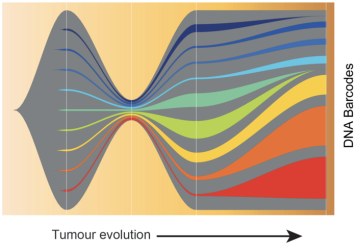

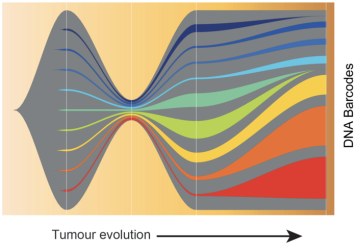

Each coloured ribbon represents a DNA barcode. As the tumour evolves, some cancer cells come to dominate the tumour, shown by the orange and red ribbons. This shows these cancer cells have a pre-existing ability to escape the immune system and can carry on growing, even after treatment

[Credit: Garvan Institute of Medical Research].

The team found that even before treatment, the cancer cells had diversified. “Some cells had already acquired the ability to evade immunity, meaning they have an innate ability to escape the immune system,” explained Associate Professor Alex Swarbrick, one of the study’s researchers.

The cells seem to do this with parallel approaches. One way is to suppress the action of killer T cells, which would usually destroy harmful cells. The other is to reduce the expression of MHC1 on cells, which act as a flag for the immune system to recognise harmful cells.

The researchers also looked at the genetics of the cells, but there were no genes found to be associated, suggesting epigenetics might be at play.

Related topics

DNA, Epigenetics, Immuno-oncology, Immunotherapy

Related conditions

Breast cancer

Related organisations

Garvan Institute of Medical Research

Related people

Associate Professor Alex Swarbrick