What is the link between serotonin and heart valve disease?

Posted: 3 February 2023 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

US researchers found that serotonin impacts the mitral valve in the heart which can lead to heart valve disease.

Serotonin can impact the mitral valve of the heart and potentially accelerate a cardiac condition known as degenerative mitral regurgitation, according to a new study led by researchers at Columbia University’s Department of Surgery in collaboration with the Paediatric Heart Valve Centre at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), the University of Pennsylvania, and the Valley Hospital Heart Institute, all US.

Serotonin binds to specific receptors on the surface of a cell, sending a signal to the cell to act accordingly. A protein known as the serotonin transporter (SERT or 5-HTT) moves serotonin into the cell to be reabsorbed and recycled, a process known as serotonin reuptake.

Degenerative mitral regurgitation (DMR) is one of the most common types of heart valve disease. The mitral valve is located between the left atrium and left ventricle of the heart. It closes tightly when the heart contracts to prevent blood from leaking back into the left atrium.

Biomarkers aren’t just supporting drug discovery – they’re driving it

FREE market report

From smarter trials to faster insights, this report unpacks the science, strategy and real-world impact behind the next generation of precision therapies.

What you’ll unlock:

- How biomarkers are guiding dose selection and early efficacy decisions in complex trials

- Why multi-omics, liquid biopsy and digital tools are redefining the discovery process

- What makes lab data regulatory-ready and why alignment matters from day one

Explore how biomarkers are shaping early drug development

Access the full report – it’s free!

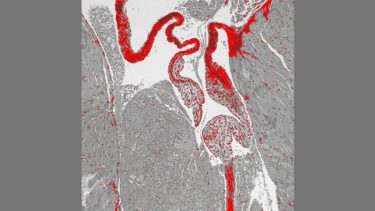

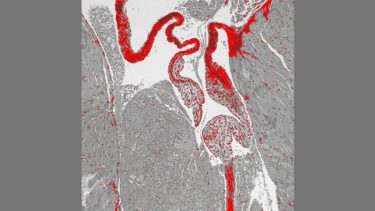

This image shows the mitral valve of the heart of a mouse that lacks the serotonin transporter (SERT) gene. The valve was stained with prico-sirius red to show collagen. SERT knockout mice had a thickened mitral valve compared to normal mice. (Credit: Columbia University Irving Medical Centre)

In DMR, the shape of the mitral valve becomes distorted, preventing the valve from closing completely. This allows blood to leak back toward the lungs (regurgitation), limiting the amount of oxygen-rich blood moving through the heart to the rest of the body.

The researchers, published in Science Translational Medicine, studied in vivo mouse models using transgenic mice lacking the SERT gene and normal mice. They discovered that mice without a SERT gene developed thicker mitral valves and that normal mice treated with high doses of SSRIs also developed thickened mitral valves.

Using genetic analysis, they identified genetic variants in the SERT gene region 5-HTTLPR that affect SERT activity. They found that a “long” variant of 5-HTTLPR makes SERT less active in the mitral valve cells, especially when there are two copies (one maternal and one paternal). DMR patients with the “long-long” variant needed mitral valve surgery more often than those with other variants.

Mitral valve cells from DMR patients with the “long-long” variant were more prone to react to serotonin by producing more collagen, changing the shape of the mitral valve. Additionally, mitral valve cells with the “long-long” variant of 5-HTTLPR were more sensitive to fluoxetine than those with other variants.

The study indicates that for DMR patients with the “long-long” variant, taking SSRIs lowers SERT activity in the mitral valve. The researchers suggested testing DMR patients for potential low SERT activity by genotyping them for 5-HTTLPR, which can be determined easily from a DNA sample obtained from the blood or a mouth swab.

“Assessing patients with DMR for low SERT activity may help identify patients who may need mitral valve surgery earlier,” said Dr Giovanni Ferrari, from Columbia University’s Department of Surgery. “Promptly fixing a mitral valve that is very leaky would protect the heart and could prevent congestive heart failure.”

There was no negative effect with normal doses of SSRIs or the “long-long” variant in cells from healthy human mitral valves.

“A healthy mitral valve can probably stand low SERT activity without deforming,” explained Ferrari. “It is unlikely that low SERT can cause degeneration of the mitral valve by itself. Once the mitral valve has started to degenerate, it may be more susceptible to serotonin and low SERT.”

Additional research may help determine if DMR patients who respond well to SSRIs should be regularly seen to assess progression of mitral degeneration, and whether patients who are not responding well to SSRIs should consider switching to a non-SSRI antidepressant rather than raising the dose of the SSRI.

Related topics

Drug Targets, Genetic Analysis, Genomics, In Vivo, Targets

Related conditions

degenerative mitral regurgitation, heart valve disease

Related organisations

Columbia University, Pennsylvania University, the Paediatric Heart Valve Centre at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), the Valley Hospital Heart Institute

Related people

Dr Giovanni Ferrari