CBD compounds could reverse opioid overdoses

Posted: 4 April 2023 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

US researchers have studied (cannabidiol) CBD as a solution for opioid overdoses, instead of a popular opioid antidote.

US scientists are now looking to cannabidiol (CBD), a component of marijuana, as a possible alternative to a popular opioid antidote.

There has been a recent push in the US to make naloxone — a fast-acting opioid antidote — available without a prescription. This medication has saved lives, but it’s less effective against powerful synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl.

On March 28 2023, a team reported that compounds based on CBD that reduce fentanyl binding and boost the effects of naloxone, at the American Chemical Society (ACS) hybrid meeting.

Reduce preclinical failures with smarter off-target profiling

24 September 2025 | 15:00PM BST | FREE Webinar

Join this webinar to hear from Dr Emilie Desfosses as she shares insights into how in vitro and in silico methods can support more informed, human-relevant safety decisions -especially as ethical and regulatory changes continue to reshape preclinical research.

What you’ll learn:

- Approaches for prioritizing follow-up studies and refining risk mitigation strategies

- How to interpret hit profiles from binding and functional assays

- Strategies for identifying organ systems at risk based on target activity modulation

- How to use visualization tools to assess safety margins and compare compound profiles

Register Now – It’s Free!

“Fentanyl-class compounds account for more than 80 percent of opioid overdose deaths, and these compounds are not going anywhere” said Dr Alex Straiker, the project’s co-principal investigator. “Given that naloxone is the only drug available to reverse overdoses, I think it makes sense to look at alternatives.”

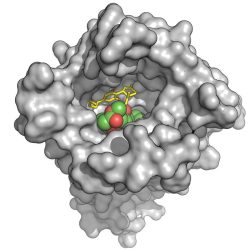

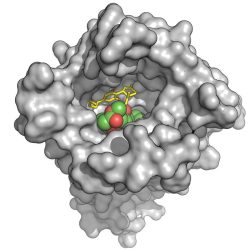

CBD (yellow stick structure) interferes with binding of an opioid (green and red) by stabilizing an opioid receptor (gray) in its inactive form. (Credit: Charles Kuntz)

A new option could take one of two forms, according to Dr Michael VanNieuwenhze, the other co-principal investigator for the project.

“Ideally, we would like to discover a more potent replacement for naloxone,” VanNieuwenhze explained. “However, finding something that works synergistically with it, reducing the amount needed to treat an overdose, would also be a success.”

Compared to other compounds in this class, such as heroin or morphine, fentanyl and its other synthetic relatives bind more tightly to opioid receptors in the brain. Naloxone reverses an overdose by competing with the drug molecules for the same binding sites on the receptors. Fentanyl binds so readily, so it has a leg up on naloxone, and growing evidence suggests that reversing these kinds of overdoses may require multiple doses of the antidote.

At this point, researchers have exhaustively studied the strategy naloxone takes, but they have yet to find any way to improve on its performance.

Earlier research suggesting that CBD can interfere with opioid binding inspired the current effort. In research published in 2006, a group based in Germany concluded that CBD hampered opioid binding indirectly, by altering the shape of the receptor. When used with naloxone, they found CBD accelerated the medication’s effect, forcing the receptors to release opioids. To augment these effects, Jessica Gudorf, a graduate student in VanNieuwenhze’s group, altered CBD’s structure to generate derivatives.

Taryn Bosquez-Berger, a graduate student in Straiker’s group, tested these new compounds in cells with a substance called DAMGO, an opioid used only in lab studies. To measure their success, she monitored a molecular signal that diminishes when this type of drug binds. Armed with feedback from these experiments, Gudorf refined the structures she generated.

In the end, they narrowed the field to 15, which they tested at varying concentrations against fentanyl, with and without naloxone. Several derivatives could reduce fentanyl binding even at what Bosquez-Berger described as “incredibly low” concentrations, while also outperforming naloxone’s opioid-blocking performance. Two of these also showed a synergistic effect when combined with the antidote.

The team has since begun testing the most successful derivatives in mice. In these experiments, they are investigating whether these compounds alter behaviours associated with taking fentanyl.

“We hope our approach leads to the birth of new therapeutics, which, in the hands of emergency personnel, could save even more lives,” Bosquez-Berger concluded.

Related topics

Cannabinoids, Drug Repurposing, Targets

Related conditions

Opioid addiction, Opioid overdose

Related organisations

The American Chemical Society (ACS)

Related people

Dr Alex Straiker, Dr Michael VanNieuwenhze, Jessica Gudorf, Taryn Bosquez-Berger