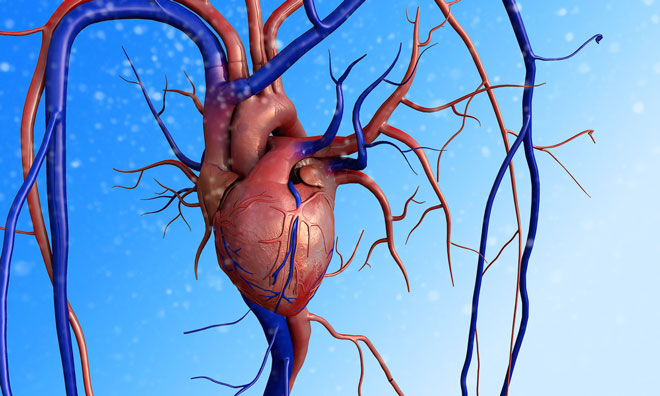

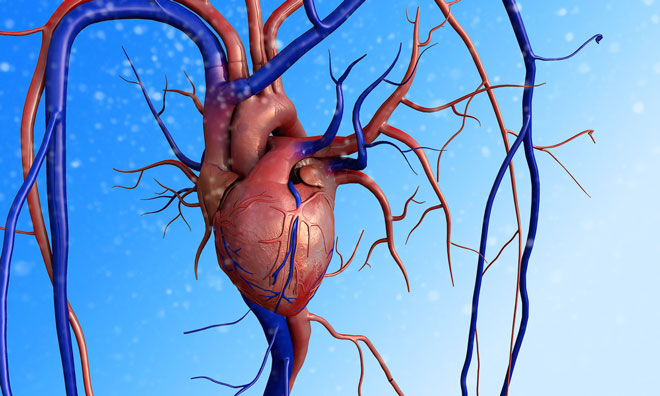

New organoid emulates development of the human heart

Posted: 7 April 2023 | Ria Kakkad (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

The team are the first researchers in the world to successfully create an organoid containing both heart muscle cells and cells of the outer layer of the heart wall.

A team at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), Germany, has induced stem cells to create an organoid that can emulate the development of the human heart. It will permit the study of the earliest development phase of our heart and facilitate research on diseases. Details were recently published in Nature Biotechnology.

The human heart starts forming approximately three weeks after conception. Findings from animal studies are not fully transferable to humans so the newly developed organoid could prove helpful to researchers.

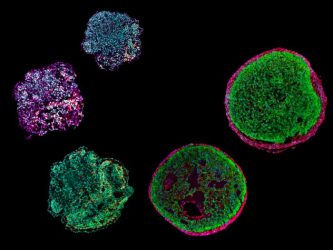

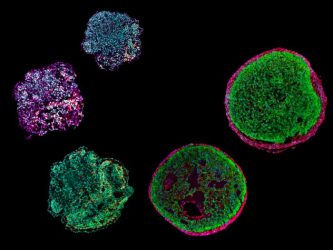

The team have developed a method for making a sort of “mini-heart” using pluripotent stem cells. Around 35,000 cells are spun into a sphere in a centrifuge. Over a period of several weeks, different signalling molecules are added to the cell culture under a fixed protocol.

The resulting organoids are about half a millimetre in diameter. Although they do not pump blood, they can be stimulated electrically and can contract like human heart chambers. The team are the first researchers in the world to successfully create an organoid containing both heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) and cells of the outer layer of the heart wall (epicardium). In the young history of heart organoids – the first were described in 2021 – researchers had previously created only organoids with cardiomyocytes and cells from the inner layer of the heart wall (endocardium).

“To understand how the heart is formed, epicardium cells are decisive,” said Dr Anna Meier, first author of the study. “Other cell types in the heart, for example in connecting tissues and blood vessels, are formed from these cells. The epicardium also plays a very important role in forming the heart chambers.” The team has appropriately named the new organoids “epicardioids”.

A team at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) has induced stem cells to emulate the development of the human heart. The result is a sort of “mini-heart” known as an organoid. It will permit the study of the earliest development phase of our heart and facilitate research on diseases [Credit: Alessandra Moretti / TUM].

Along with the method for producing the organoids, the team has reported its first new discoveries. Through the analysis of individual cells, they have determined that precursor cells of a type only recently discovered in mice are formed around the seventh day of the development of the organoid. The epicardium is formed from these cells. “We assume that these cells also exist in the human body – if only for a few days,” said Professor Alessandra Moretti.

These insights may also offer clues as to why the foetal heart can repair itself, a capability almost entirely absent in the heart of an adult human. This knowledge could help to find new treatment methods for heart attacks and other conditions.

The team also showed that the organoids can be used to investigate the illnesses of individual patients. Using pluripotent stem cells from a patient suffering from Noonan syndrome, the researchers produced organoids that emulated characteristics of the condition in a Petri dish. Over the coming months the team plans to use comparable personalised organoids to investigate other congenital heart defects.

With the possibility of emulating heart conditions in organoids, drugs could be tested directly on them in the future. “It is conceivable that such tests could reduce the need for animal experiments when developing drugs,” said Moretti.

Related topics

Animal Models, Cell Cultures, Disease Research, Genomics, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), Organoids

Related organisations

Technical University of Munich (TUM)

Related people

Dr Anna Meier, Professor Alessandra Moretti