Researchers identify new genetic risk factors for endometrial cancer

Posted: 3 May 2016 | Victoria White, Digital Content Producer | No comments yet

Researchers also looked at how the identified gene regions might be increasing the risk of cancer, and these findings may lead to new treatments…

Researchers have identified five new gene regions that increase a woman’s risk of developing endometrial cancer, taking the number of known gene regions associated with the disease to nine.

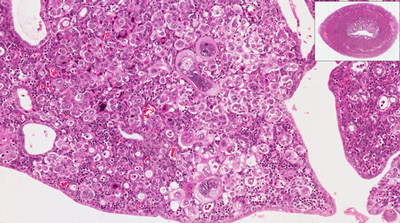

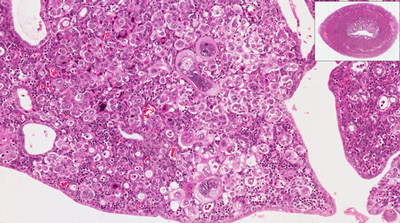

Endometrial cancer affects the lining of the uterus. It is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer in UK women, with around 9,000 new cases being diagnosed each year.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge, Oxford University and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane studied the DNA of over 7,000 women with endometrial cancer and 37,000 women without cancer to identify genetic variants that affected a woman’s risk of developing the disease. The findings help paint a clearer picture of the genetic causes of endometrial cancer in women, particularly where there no strong family history of cancer.

Dr Deborah Thompson from the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge, explained: “Prior to this study, we only knew of four regions of the genome in which a common genetic variant increases a woman’s risk of endometrial cancer.

“In this study we have identified another five regions, bringing the total to nine. This finding doubles the number of known risk regions, and therefore makes an important contribution to our knowledge of the genetic drivers of endometrial cancer.

“Interestingly, several of the gene regions we identified in the study were already known to contribute to the risk of other common cancers such as ovarian and prostate.”

Implications for future treatments

The study also looked at how the identified gene regions might be increasing the risk of cancer, and these findings have implications for the future treatment of endometrial cancer patients.

“As we develop a more comprehensive view of the genetic risk factors for endometrial cancer, we can start to work out which genes could potentially be targeted with new treatments down the track,” said Associate Professor Amanda Spurdle from QIMR Berghofer.

“In particular, we can start looking into whether there are drugs that are already approved and available for use that can be used to target those genes.”

“It might also provide clues into the faulty molecules that play an important role in womb cancer, leading to potential new treatments. More than a third of womb cancer cases in the UK each year could be prevented, and staying a healthy weight and keeping active are both great ways for women to reduce the risk.”

Related organisations

Oxford University, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, University of Cambridge