Predicting pancreatic cancer metastasis

Posted: 2 July 2024 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Molecular, cellular and metabolic analyses of liver biopsies identified markers that may predict subsequent metastasis of pancreatic cancer.

Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine, alongside international team, identified cellular and molecular markers in liver biopsies that could be used to predict whether and when pancreatic cancer will metastasise to a patient’s liver or elsewhere. This may help clinicians to personalise treatment before cancer cells have the chance to metastasise.

After initial diagnosis, only 10 percent of people with pancreatic cancer will survive more than two years. Dr David Lyden, the Stavros S. Niarchos Professor in Pediatric Cardiology and professor of paediatrics and of cell and developmental biology at Weill Cornell Medicine, stated: “If we can predict the timing and location of metastases, that could be a real game changer in treating pancreatic cancer, particularly patients at high metastatic risk.”

In 2015, Dr Lyden and his team found that pancreatic cancer cells release factors that travel to distant organs, frequently the liver, to begin a pre-metastatic niche for new tumours to grow. In the new study, Dr Lyden collaborated with lead author Dr Linda Bojmar, an adjunct assistant professor of molecular biology research in paediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and assistant professor of clinical and experimental medicine at Linköping University, to discover how these alterations prime their new location for tumour growth.

With researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center the team acquired liver biopsies from 49 individuals who had surgical treatment for early-stage pancreatic cancer. As well as this, they collected liver biopsies from 19 people who underwent a similar operation for conditions unrelated to cancer, such as the removal of benign pancreatic cysts.

Molecular, cellular and metabolic analyses of these samples were conducted to decide whether they could identify hallmarks that preceded, or potentially prevented, later metastases in the patients. It was observed that the livers of recurrence-free survivors, who showed no signs of cancer spread after a follow-up period of at least three years, resembled the livers of people who never had cancer.

However, in those who developed liver metastases within six months of diagnosis, which is a patient group that has poor prognosis with limited therapeutic options, the livers had a significant abundance of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). NETs are strongly associated with future metastases, but develop very early in the course of disease, so radiological imaging soon could be able to detect them and pinpoint patients in danger of this aggressive spread. Dr Lyden explained: “These individuals could then receive a full course of chemotherapy or, if the metastases are detected when only a few appear, perhaps the secondary tumours could be surgically removed.” Furthermore, the team are exploring whether drugs that digest the DNA which forms the NETs could prevent liver metastases.

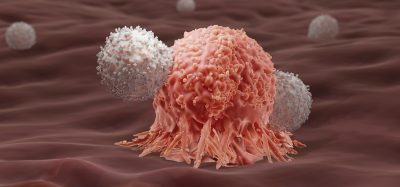

The study included two other categories of patients. The first were those who would go on to develop later metastases to the liver, and the second were those who would have the cancer spread to other sites. Individuals whose cancers spread to organs other than the liver, demonstrated a powerful immune response fighting the cancer, with an infiltration of T cells and natural killer cells and many activated immune-regulatory genes. These individuals who are prone to developing metastases outside the liver may benefit from immunotherapy to boost their ongoing anti-tumour immune response. In those whose livers had subsequent metastases also accumulated immune cells, yet the cells exhibited signs of metabolic exhaustion.

Moving forwards, the team aim to validate their discovery in a larger cohort of patients with pancreatic cancer and evaluate if this approach could be useful with other newly diagnosed cancers. Dr Robert Schwarz, associate professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, concluded: “We hope to develop a tool for predicting which patients with colorectal cancer will go on to develop liver metastases based on the cellular, molecular and metabolic profiles of their liver biopsies.”

This study was published in Nature Medicine.

Related topics

Analysis, Cancer research, Molecular Targets, Oncology, Personalised Medicine

Related conditions

Cancer Research, metastatic cancer, Pancreatic cancer

Related organisations

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Weill Cornell Medicine