Wildlife conservation plans must consider Lyme disease risk

Posted: 19 May 2017 | Niamh Marriott (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

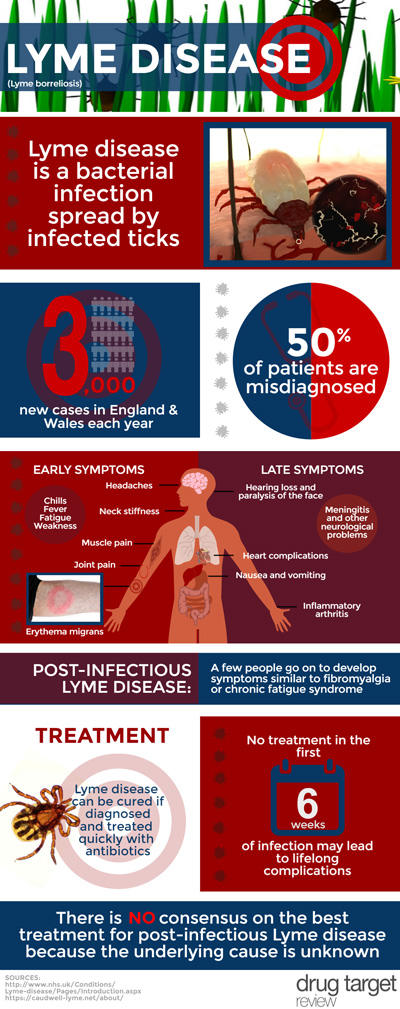

Lyme disease – an infection contracted from the bite of an infected tick– is an important emerging disease in the UK, and is increasing in incidence in people in the UK and large parts of Europe and North America.

A new study found that some types of conservation action could increase the abundance of ticks, which transmit diseases like Lyme disease.

The research – led by the University of Glasgow in collaboration with Scottish Natural Heritage, the James Hutton Institute and Public Health England – examined how conservation management activities could affect tick populations, wildlife host communities, the transmission of the Borrelia bacteria that can cause Lyme disease and, ultimately, the risk of contracting Lyme disease.

Biodiversity

The study found that managing the environment for conservation and biodiversity has many positive effects, including benefits for human health and wellbeing from spending time in nature; however the researchers suggested that there should be consideration of disease vectors such as ticks and mosquitoes in conservation management decisions.

Lead author Dr Caroline Millins, from the University of Glasgow’s School of Veterinary Medicine and Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine (BAHCM), said: “We identified several widespread conservation management practices which could affect Lyme disease risk: the management of deer populations, woodland regeneration, urban greening and control of invasive species.

“We found that some management activities could lead to an increased risk of Lyme disease by increasing the habitat available for wildlife hosts and the tick vector. These activities were woodland regeneration and biodiversity policies which increase the amount of forest bordering open areas as well as urban greening.

“However, if deer populations are managed alongside woodland regeneration projects, this can reduce tick populations and the risk of Lyme disease.”

Deer are often key to maintaining tick populations, but do not become infected with the bacteria. Previous research by co-author Lucy Gilbert of The James Hutton Institute has shown that greatly reducing deer densities by exclusion fencing or culling can reduce tick density and therefore Lyme disease risk.

Senior author Dr Roman Biek, University of Glasgow’s BAHCM, said: “Widespread management activities can potentially teach us a lot about how changes to the environment can affect the chances of humans coming into contact with ticks and with the pathogens ticks transmit. We recommend that monitoring ticks and pathogens should accompany conservation measures such as woodland regeneration and urban greening projects. This will allow appropriate guidelines and mitigation strategies to be developed, while also helping us to better understand the processes leading to higher Lyme disease risk.”

Co-author Professor Des Thompson, Principal Adviser on Science and Biodiversity with Scottish Natural Heritage, commented: “This is the sort of vital research we need to act on in order to advise Government on the best practices for enhancing wildlife whilst minimising risks to human health. The Scottish Government’s 2020 plan for Scotland’s Biodiversity requires this integrated approach, bringing human health and wildlife management sectors together.”

The paper was funded by the BBSRC.

Related topics

Analysis, Funding, public safety

Related conditions

Lyme disease

Related organisations

James Hutton Institute, Public Health England (PHE), Scottish Natural Heritage, University of Glasgow

Related people

Dr Caroline Millins, Dr Roman Biek, Professor Des Thompson