Researchers uncover protective role of oestrogen against type-2 diabetes

Posted: 9 April 2018 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Scientists in Switzerland reveal the mechanisms behind the protective role of oestrogen against developing type 2 diabetes.

Epidemiological data indicates that the onset of type-2 diabetes in women increases significantly after menopause. A team of Swiss scientists has investigated the reason for this, highlighting the surprisingly protective role that oestrogen plays in preventing the disease. Their study showed that a woman undergoing hormone replacement therapy is up to 35% less likely to develop type 2 diabetes than a woman without treatment.

By elucidating how oestrogen affects two of the hormones involved in glucose homeostasis (stability) – glucagon and GLP1 – researchers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) prove the value of oestrogen supplementation from the onset of menopause. The research also shows that only one of the three oestrogen receptors seems to be involved in this mechanism. This could ultimately provide therapies targeted to a specific molecule that would prevent some of the side effects often experienced with a too powerful hormonal therapy.

It is widely acknowledged among diabetes experts that pre-menopausal women are less likely than men to develop type-2 diabetes. However, post-menopause there is a distinct reversal of this trend, highlighting the protective role of women’s sexual hormones and especially oestrogens. Until now, however, their specific effect on metabolism was unknown.

Oestrogen’s effect on glucagon

In an attempt to understand this function, the team – led by Jacques Philippe, Diabetes specialist at UNIGE Faculty of Medicine and Head of the HUG Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Hypertension and Nutrition – focused their attention on a different hormone, glucagon.

“A number of scientists are working on the effect of oestrogens on pancreatic insulin-producing cells,” says Sandra Handgraaf, a researcher at the Faculty of Medicine and the first author of this work. “But its effect on glucagon-producing cells, another hormone regulating blood sugar, had never been explored before.

“Indeed, if the pancreas secretes insulin, it also secretes glucagon – a hormone with the opposite effect: insulin captures sugar, while glucagon releases it. Diabetes is therefore due to an imbalance between these two hormones controlling the sugar level in the blood.”

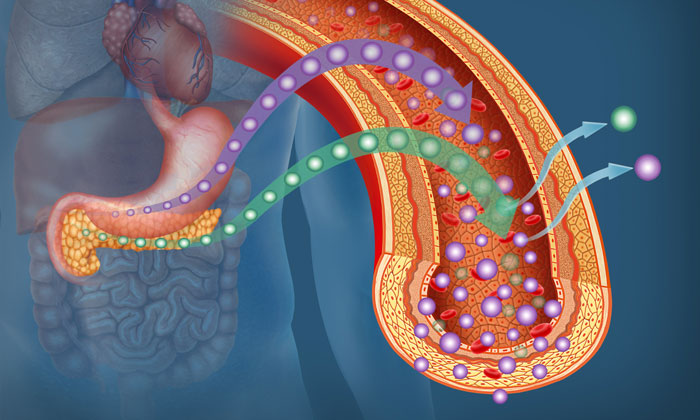

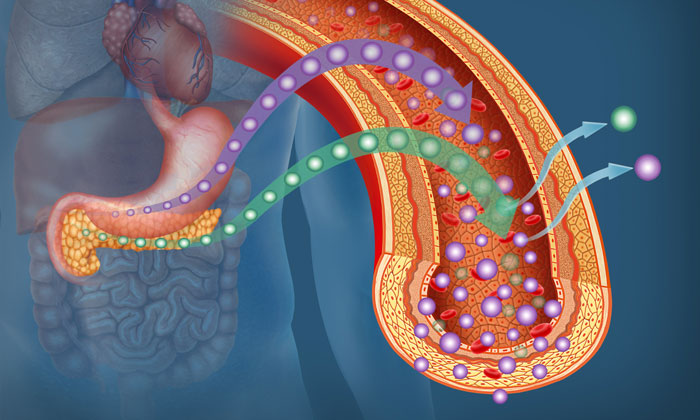

Oestrogen impacts GLP1 hormone as well as insulin

Oestrogen administration to post-menopausal female mice led the Geneva scientists to make a first observation: they identified an increased tolerance to glucose, which is correlated to a lower risk of diabetes. However, if the effect on insulin was expected, the effect on glucagon – and especially GLP1, an intestinal and pancreatic hormone that increases insulin production – was unexpected. These results confirmed the sensitivity to oestrogen of pancreatic alpha cells, which then secrete less hyperglycaemic glucagon, but more GLP1. Also released by the intestine during the absorption of meal, this hormone stimulates the secretion of insulin, inhibits the secretion of glucagon and induces the feeling of satiety. The lack of GLP1 is therefore an essential element in the onset of diabetes. The role it plays represents a major explanation of the protection of women regarding diabetes onset before menopause.

“This first observation was already interesting,” explains Sandra Handgraaf, “but we went a step further: indeed, the gut harbours cells called L cells that are very similar to pancreatic alpha cells and whose main function is precisely to produce GLP1. We also observed a strong increase in the production of GLP1 in the gut cells, thus proving the crucial role of the intestine in the control of carbohydrate balance and the influence of oestrogens on the entire metabolisms at stake”. These results were also confirmed on human cells and tissue samples.

Negating cardiovascular risks of hormonal replacement therapy

Hormonal substitution treatments are often subject to negative publicity, mainly because of the cardiovascular risks associated with them. However, study leader Philippe stresses: “If hormonal treatment is taken more than 10 years after menopause, the cardiovascular risk is effectively increased. In the context of diabetes, an oestrogenic treatment allows to avoid, in all cases, the explosion of female diabetes cases. These treatments, well administered, can really add value for women’s health.”

In their study, the Geneva researchers were also able to dissect the fine cellular mechanisms involved: Of the three oestrogen receptors, only one is significantly involved in this protective effect. It would therefore be possible to develop a molecule that only activates this particular receptor, providing a far more targeted effect. “One could imagine a treatment that, without the side effects of a little too powerful hormonal therapy, would also address men”, concludes Handgraaf.

This study was published in JCI Insight.

Related topics

Disease Research

Related conditions

Type-2 diabetes

Related organisations

Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), University of Geneva

Related people

Jacques Philippe, Sandra Handgraaf