New lead for Alzheimer’s research proposed

Posted: 15 August 2018 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Researchers identified a connection between the way neurons handle iron and mutations that may cause inherited Alzheimer’s disease…

A team of scientists have suggested a link between the rare genetic mutations that cause Alzheimer’s disease and iron in our cells.

Alzheimer’s disease is known to be the most common cause of dementia, and with 850,000 people in the UK, and 46.8 million people worldwide suffering from dementia, a successful course of treatment is needed.

The researchers propose that the way cells in the body handle iron could be a reason why mutations occur and why Alzheimer’s and dementia develops.

Biomarkers aren’t just supporting drug discovery – they’re driving it

FREE market report

From smarter trials to faster insights, this report unpacks the science, strategy and real-world impact behind the next generation of precision therapies.

What you’ll unlock:

- How biomarkers are guiding dose selection and early efficacy decisions in complex trials

- Why multi-omics, liquid biopsy and digital tools are redefining the discovery process

- What makes lab data regulatory-ready and why alignment matters from day one

Explore how biomarkers are shaping early drug development

Access the full report – it’s free!

“For 20 years most scientists have believed that a small protein fragment, amyloid beta, causes Alzheimer’s disease,” said Associate Professor Michael Lardelli, from the School of Biological Sciences, at the University of Adelaide.

“Clearing out amyloid beta from the brains of people who are developing Alzheimer’s disease can slow their rate of cognitive decline. But, so far, nothing has been able to stop the relentless progression of the disease,” he said.

After a conversation between Prof Lardelli, Dr Amanda Lumsden from the South Australian Health and Medicinal Research Institute and Flinders University, and Dr Morgan Newman from the University of Adelaide, the inspiration for this theory began.

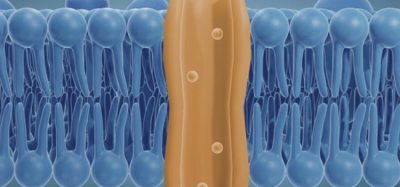

Dr Lumsden studied the action of cells that use iron, with researchers at the University of Adelaide studying the gene mutations that cause Alzheimer’s disease.

The team suggest that changes in the brain seen in inherited Alzheimer’s disease could result from the way neurons in the brain handle iron.

“Cells need iron to survive. In particular, iron is essential for the tiny powerhouses of all cells – the mitochondria – to generate most of the energy that keeps cells functioning,” said Prof Lardelli.

“The genes mutated in inherited Alzheimer’s disease seem likely to affect how iron enters neurons, how it is recycled within neurons, and how it is exported from neurons.

“Since neurons have such huge energy needs, disturbing the way they handle iron can have serious, long-term consequences.

“Furthermore, iron is a key player in inflammation and in the production of damaging molecules named ‘reactive oxygen species’, and both occur at high levels in brains with Alzheimer’s disease,” said Prof Lardelli.

Despite the researchers identifying connections between iron and Alzheimer’s disease, further investigation is still required to fully understand the mechanisms behind how mutations affect cellular actions towards iron. As such, the team have cautioned people about changing their diets, as their theory relates to how cells handle iron – not the amount of iron in an individual’s diet.

The study was published in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Related topics

Disease Research, Drug Development, Research & Development

Related conditions

Alzheimer’s disease

Related organisations

Adelaide University, Flinders University, South Australian Health and Medicinal Research Institute

Related people

Associate Professor Michael Lardelli, Dr Amanda Lumsden, Dr Morgan Newman