Study shows that immune cells determine growth of certain tumours

Posted: 4 June 2019 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

A new study shows that the growth rate of a tumour does not depend solely on how quickly the cancer cells can divide.

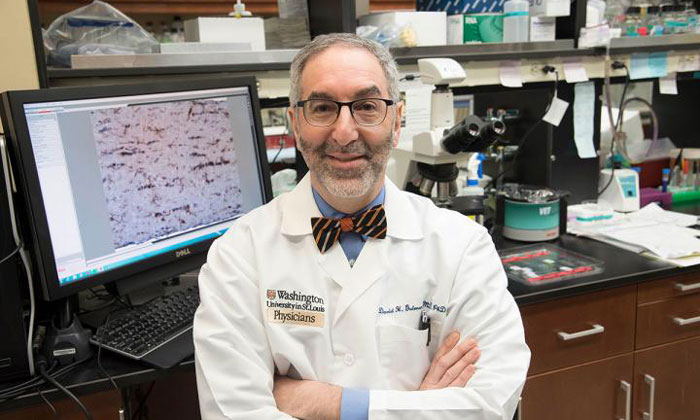

David H Gutmann, MD, PhD, and colleagues at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis studying brain tumours in mice discovered that tumours grow most rapidly if they can enlist the aid of immune cells. The findings suggest that therapies targeting immune cells could potentially treat some kinds of brain tumours (credit: Washington University).

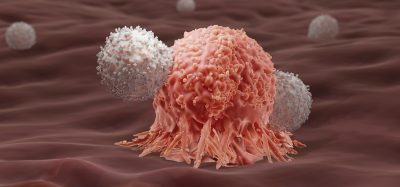

By examining brain tumors in mice, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine have discovered that immune cells that should be defending the body can actually aid tumour cells instead. In fact, the more immune cells a tumour can recruit to its side, the faster the tumour grows.

The findings suggest that targeting immune system cells could potentially slow brain tumour growth in people with the genetic condition neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

“This gives us another way to attack these tumours beyond merely killing the cancer cells – namely, interrupting the communication between tumour cells and immune system cells,” said senior author David H Gutmann, MD, PhD, the Donald O. Schnuck Family Professor of Neurology and director of the Washington University Neurofibromatosis Center.

To better understand why some tumours grow faster than others, first author Xiaofan Guo, MD, a graduate student in Gutmann’s research laboratory, created five mouse strains with different genetic changes in the NF1 gene and elsewhere in the mouse’s genome.

The five strains varied in tumour development and size. However, when the researchers isolated tumour cells from the mice and grew them in a dish, they found little difference in tumour cell growth. The growth rates and other properties of the cancer cells were very similar, no matter which mutation the tumour cells carried.

What did correlate with overall tumour proliferation in mice was the presence of two kinds of immune cells – microglia and T cells – within the tumours. Guo and former postdoctoral research fellow Yuan Pan, PhD, discovered that the tumour cells themselves were releasing immune system proteins that attracted immune cells to the tumour

The researchers now are trying to take advantage of this relationship to find new ways to treat brain tumours in people with NF1. One strategy is to slow tumour growth by preventing microglia or T cells from providing support to the cancer cells. However, a more ambitious strategy is to reprogramme the T cells to no longer aid tumour cell growth.

“The idea is to use T cells as Trojan horses,” said Gutmann. “We’re trying to change the T cells so that when they enter the brain, instead of promoting the tumour, they shut it down.”

This study was published in the journal Neuro-Oncology.

Related topics

Analysis, Cell Cultures, Immuno-oncology, Research & Development, T cells

Related conditions

Brain cancer

Related organisations

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Related people

David H Gutmann MD PhD, Xiaofan Guo MD, Yuan Pan PhD