Researchers design first artificial ribosome

Posted: 30 July 2015 | Victoria White

Researchers have engineered a tethered ribosome that may enable the production of new drugs and next-generation biomaterials…

Researchers have engineered a tethered ribosome that works nearly as well as the authentic cellular component, or organelle, that produces all the proteins and enzymes within the cell.

The engineered ribosome may enable the production of new drugs and next-generation biomaterials and lead to a better understanding of how ribosomes function.

The artificial ribosome, called Ribo-T, was created in the laboratories of Alexander Mankin, director of the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) College of Pharmacy’s Centre for Biomolecular Sciences, and Northwestern University’s Michael Jewett, assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering. The human-made ribosome may be able to be manipulated in the laboratory to do things natural ribosomes cannot do.

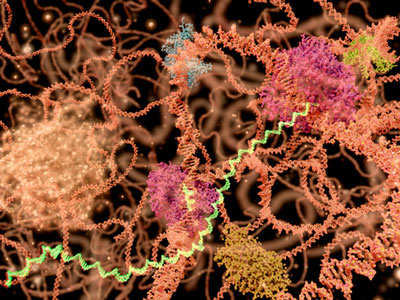

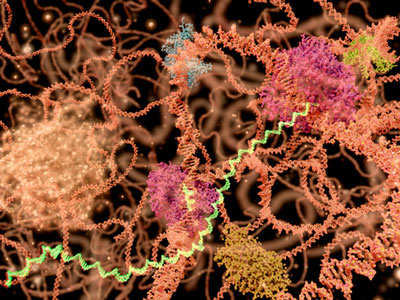

When a cell makes a protein, mRNA (messenger RNA) is copied from DNA. The ribosomes’ two subunits, one large and one small, unite on mRNA to form the functional unit that assembles the protein in a process called translation. Once the protein molecule is complete, the ribosome subunits — both of which are themselves made up of RNA and protein — separate from each other.

Mankin, Jewett and their colleagues were frustrated in their investigations by the ribosomes’ subunits falling apart and coming together in every cycle of protein synthesis. Could the subunits be permanently linked together? The researchers devised a novel designer ribosome with tethered subunits – Ribo-T. Ribo-T may be able to be tuned to produce unique and functional polymers for exploring ribosome functions or producing designer therapeutics — and perhaps one day even non-biological polymers.

No one has ever developed something of this nature.

Ribo-T can support growth in the absence of wild-type ribosomes

“What we were ultimately able to do was show that by creating an engineered ribosome where the ribosomal RNA is shared between the two subunits and linked by these small tethers, we could actually create a dual translation system,” Jewett said.

“It was surprising that our hybrid chimeric RNA could support assembly of a functional ribosome in the cell. It was also surprising that this tethered ribosome could support growth in the absence of wild-type ribosomes,” he said.

Ribo-T worked even better than Mankin and Jewett believed it could. Not only did Ribo-T make proteins in a test-tube, it was able to make enough protein in bacterial cells that lacked natural ribosomes to keep the bacteria alive.

Jewett and Mankin were surprised by this. Scientists had previously believed that the ability of the two ribosomal subunits to separate was required for protein synthesis.

“Our new protein-making factory holds promise to expand the genetic code in a unique and transformative way, providing exciting opportunities for synthetic biology and biomolecular engineering,” Jewett said.

“This is an exciting tool to explore ribosomal functions by experimenting with the most critical parts of the protein synthesis machine, which previously were ‘untouchable,'” Mankin added.

The researchers describe the design and properties of Ribo-T in Nature.

Related topics

Enzymes

Related organisations

Northwestern University, University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC)