Huntington’s update: optimal treatment times and implicated molecules

Posted: 28 May 2020 | Hannah Balfour (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Two studies reveal the importance of timing in Huntington’s disease interventions and demonstrate interleukin-6 may play a protective role.

When should Huntington’s treatments begin?

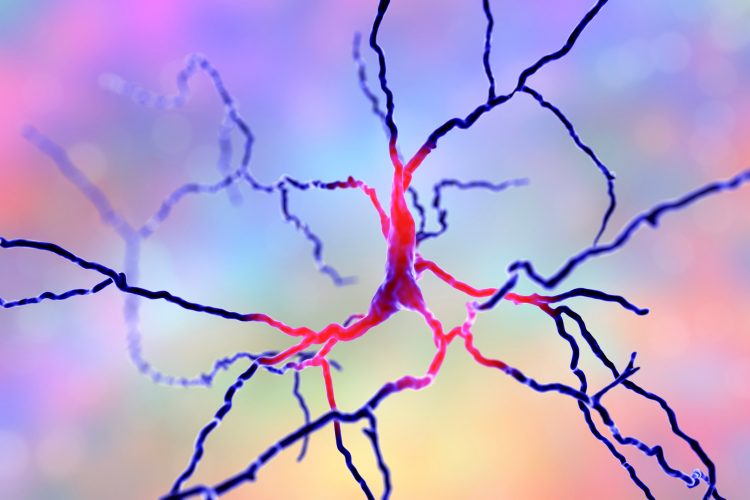

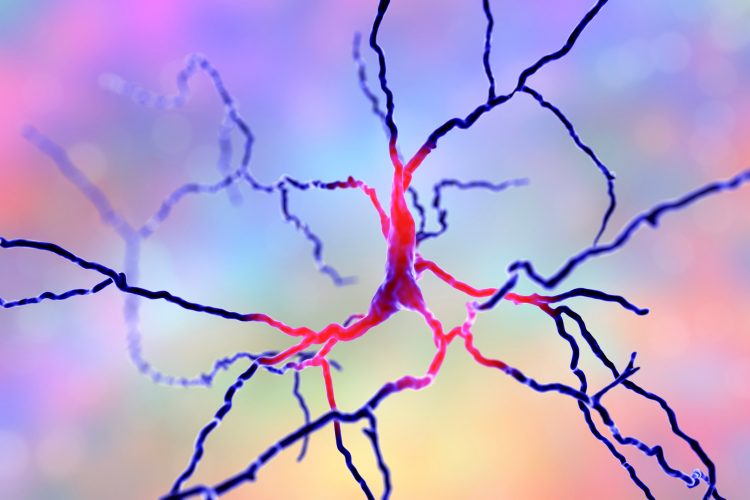

Research has revealed that brain changes in Huntington’s disease (HD) can be detected 24 years ahead of the emergence of clinical symptoms. The scientists suggest their study could be used to pinpoint the optimal time to initiate treatments, informing clinical trials.

We have found what could be the earliest Huntington’s-related changes, in a measure which could be used to monitor and gauge effectiveness of future treatments”

While there is no approved therapies to slow the progression of Huntington’s, a hereditary neurodegenerative disease, there is a genetic susceptibility test. In their study published in The Lancet Neurology, the researchers sought to identify if people who had tested positive for the genetic susceptibility to Huntington’s had detectable brain changes 24 years prior to the predicted onset of clinical symptoms.

Professor Sarah Tabrizi from the University College London (UCL) Huntington’s Disease Centre and UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, who led the study, said: “Ultimately, our goal is to deliver the right drug at the right time to effectively treat this disease – ideally we would like to delay or prevent neurodegeneration while function is still intact, giving gene carriers many more years of life without impairment.

“As the field makes great strides with the drug development, these findings provide vital new insights informing the best time to initiate treatments in the future, and represent a significant advance in our understanding of early Huntington’s.”

In collaboration, UCL, University of Cambridge and University of Iowa researchers, extensively tested 64 Huntington’s mutation carriers alongside 67 others without the mutation, acting as controls. The study included tests of thinking, behaviour, brain scans and proteins in spinal fluid.

The mutation carriers were, on average, 24 years ahead of the predicted disease onset and exhibited no cognitive or behavioural signs associated with the disease, their brain scans also showed little evidence of any changes.

However, the team identified the mutation carriers had a small increase of neurofilament light (NfL) protein, a neuronal protein that is often the product of nerve cell damage, in their spinal fluid. Approximately half (47 percent) of the carriers had NfL values above that of the control group, which correlated with their predicted time to disease onset.

Co-first author of the study, Dr Paul Zeun, from the UCL Huntington’s Disease Research Centre said: “We have found what could be the earliest Huntington’s-related changes, in a measure which could be used to monitor and gauge effectiveness of future treatments in gene carriers without symptoms.”

Co-first author of the study, Dr Rachael Scahill, also from the UCL Huntington’s Disease Research Centre added: “Other studies have found that subtle cognitive, motor and neuropsychiatric impairments can appear 10-15 years before disease onset. We suspect that initiating treatment even earlier, just before any changes begin in the brain, could be ideal, but there may be a complex trade-off between the benefits of slowing the disease at that point and any negative effects of long-term treatment.”

Interleukin-6 plays a protective role in Huntington’s disease model

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) had been thought to promote neurodegeneration in HD patients because it has been found expressed at abnormally high levels more than a decade before they exhibited clinical symptoms.

However, new research has found that Huntington’s model mice bred to lack IL-6 showed exacerbated symptoms compared to HD mice that still had it.

“If one looks back in the literature of the Huntington’s disease field many people have postulated that reductions to IL-6 would be therapeutic in HD,” said study senior author, Myriam Heiman, associate professor in Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT’s) Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and a member of The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Molecular structre of IL-6.

The paper published in Molecular Neurodegeneration tests the hypothesis that knocking out IL-6 would lessen the symptoms expressed by murine HD models. The researchers cross-bred mice engineered to model HD with mice engineered to lack IL-6 and compared the offspring’s performance on a variety of movement tasks to that of healthy mice, mice lacking only IL-6 and mice modelling HD expressing IL-6.

The results reveal the HD mice lacking IL-6 performed significantly worse than the other mouse lines, including the HD mice expressing IL-6.

To better understand the results, the team measured gene expression in all the major cell types in the striatum, the brain region most affected in HD, by sequencing RNA in thousands of individual cells in each mouse line. When they looked at the differences in gene expression in neurons between the HD mouse lines, one expressing IL-6 and the other not, they found that many genes important for synapses were significantly less expressed in the HD mice without IL-6.

“Perhaps this worsening of the phenotype is due to perturbation of those synaptic signalling pathways,” Heiman said.

Heiman concluded that while completely knocking out IL-6 has no therapeutic benefit, a level between overexpression and complete knockout may be therapeutic, and that the timing of the intervention may be crucial; in this study mice lacked IL-6 right from birth, but Heiman suggested potentially intervening to modulate IL-6 levels at some stage of adulthood may be beneficial.

The lab plans to continue to pursue that investigation.

Related conditions

Huntington's disease

Related organisations

Iowa University, MIT, University College London (UCL), University College London (UCL) Huntington's Disease Centre, University of Cambridge

Related people

Dr Paul Zeun, Dr Rachael Scahill, Myriam Heiman, Professor Sarah Tabrizi