Researchers develop first synthetic inhibitor of coagulation factor XII

Posted: 5 August 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

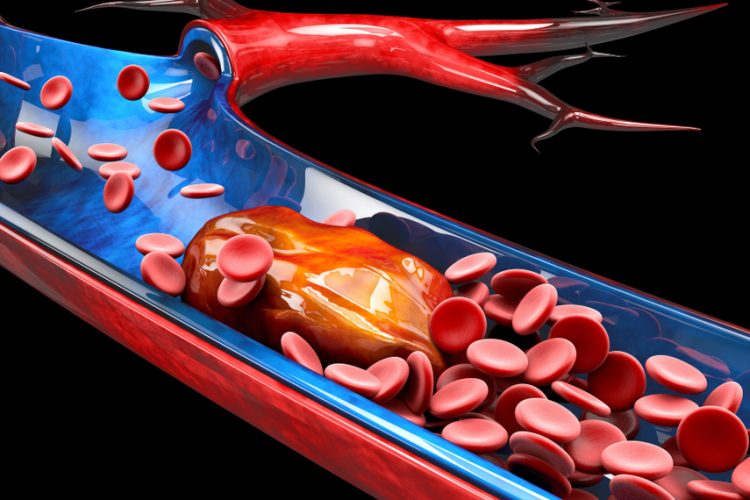

A new FXII inhibitor has been developed that efficiently blocked coagulation in a thrombosis model without increasing the risk of bleeding.

A team of scientists has developed the first synthetic inhibitor of coagulation factor XII (FXII), an enzyme that normally helps blood clot. A few years ago, research showed that mice without FXII had a very reduced risk of thrombosis without the side-effect of bleeding. The discovery triggered a race for FXII inhibitors to treat thrombosis, which the current study has made steps towards.

The study was conducted at the Laboratory of Therapeutic Proteins and Peptides of Professor Christian Heinis at École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). The researchers say their inhibitor has high potency, high selectivity and is highly stable, with a plasma half-life of over 120 hours.

“The FXII inhibitor is a variation of a cyclic peptide that we identified in a pool of more than a billion different peptides, using a technique named phage display,” said Heinis. The researchers then improved the inhibitor by replacing several of its natural amino acids with synthetic ones. “This wasn’t a quick task; it took over six years and two generations of PhD students and post-docs to complete.”

With their potent FXII inhibitor, the researchers showed that it efficiently blocks coagulation in a thrombosis model without increasing the bleeding risk. They then assessed the inhibitor’s pharmacokinetic properties, by studying the inhibitor in an artificial lung model and found that it efficiently reduced blood clotting, all without any bleeding side-effects.

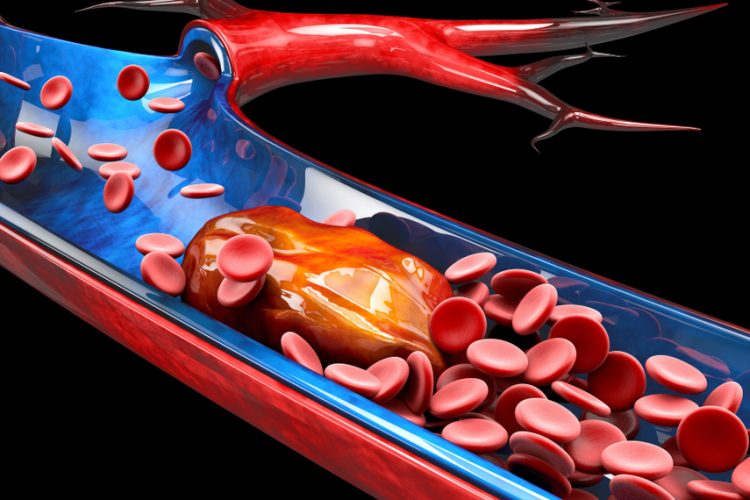

“The new FXII inhibitor is a promising candidate for safe thromboprotection in artificial lungs, which are used to bridge the time between lung failure and lung transplantation,” explained Heinis. “In these devices, contact of blood proteins with artificial surfaces such as the membrane of the oxygenator or tubing can cause blood clotting.” Known as ‘contact activation’, this can lead to severe complications or even death and limits the use of artificial lungs for longer than a few days or weeks.

However, the researchers highlight a problem which is that the inhibitor has a relatively short retention time in the body; it is too small and the kidneys would filter it out. In the context of artificial lungs, this would mean constant infusion, since suppressing blood clotting for several days, weeks or months requires a long circulation time.

Despite this, Heinis is optimistic: “We’re fixing this; we’re currently engineering variants of the FXII inhibitor with a longer retention time.”

The findings were published in Nature Communications.

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Discovery, Drug Targets, Enzymes, Research & Development, Small molecule, Target Molecule

Related conditions

thrombosis

Related organisations

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale De Lausanne (EPFL)

Related people

Professor Christian Heinis