UCLA researchers identify drug that helps fight side effect of ovarian cancer

Posted: 17 November 2015 | Victoria White

The researchers found that a drug that inhibits a receptor called the Colony-Stimulating-Factor-1 Receptor reduces ascites with minimal side effects…

UCLA researchers have found an experimental drug that can help fight a debilitating side effect of ovarian cancer.

Women who have ovarian cancer often develop a condition called ascites, which is a buildup of fluids in the abdomen. The most common treatment for ascites is puncturing the abdomen and manually draining the fluid, which is painful and risky and must be repeated every few weeks.

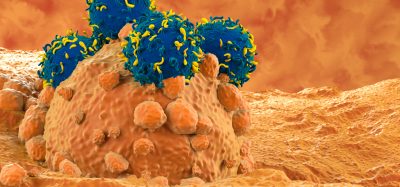

The researchers found that a drug that inhibits a receptor called the Colony-Stimulating-Factor-1 Receptor (CSF1R) reduces ascites with minimal side effects. This inhibition therapy targets not cancer cells but macrophages, a special type of immune cell, in order to prevent them from helping the cancer take root in the abdomen. In effect, the drug makes the abdominal cavity into an environment less conducive to cancer growth.

Automation now plays a central role in discovery. From self-driving laboratories to real-time bioprocessing

This report explores how data-driven systems improve reproducibility, speed decisions and make scale achievable across research and development.

Inside the report:

- Advance discovery through miniaturised, high-throughput and animal-free systems

- Integrate AI, robotics and analytics to speed decision-making

- Streamline cell therapy and bioprocess QC for scale and compliance

- And more!

This report unlocks perspectives that show how automation is changing the scale and quality of discovery. The result is faster insight, stronger data and better science – access your free copy today

Ascites is caused by a problem with the abdominal blood and lymphatic vessels that causes the blood vessels to “leak” and the lymphatic vessels, which would otherwise drain the excess fluid, to become “plugged” with cancer cells. Previous research has focused on inhibiting a protein called VEGF. However, that treatment is risky and has been reported to cause catastrophic intestinal perforation in some patients in clinical trials. By contrast, people treated with CSF1R inhibitors experienced no major side effects.

CSF1R inhibitors lessen the number of pro-tumour macrophages

“Specifically targeting the cells with CSF1R inhibitors lessens the number of pro-tumour macrophages and allows the vessels in the abdomen to become normal again, easing ascites accumulation,” said Dr Lily Wu, a professor of pharmacology, paediatrics and urology at UCLA. “All of this is accomplished without dangerous side effects or pain.”

Tumours pump out a protein called CSF-1 to recruit and change macrophages. CSF-1 hunts for the CSF1R receptor. Macrophages express CSF1R and respond to the signalling by traveling toward the tumour and becoming pro-tumour. When CSF1R was inhibited, the number of macrophages in the ascites around the tumour was vastly reduced, which, in turn made the ascites environment much less favourable to the tumour.

In an animal model, after just two weeks of treatment with the CSF1R inhibitor, the animals’ blood vessels carried blood normally instead of leaking it. Wu said this caused the ascites to at least stop accumulating, and in many cases to regress.

Going forward, Wu and her team want to try the therapy in a clinical trial. They also will explore whether the CSF1R inhibition therapy can be combined with standard ovarian cancer treatments to fight both the ascites and the cancer.

Related topics

Oncology

Related organisations

Cancer Research, UCLA