Rhesus macaque model of Alzheimer’s disease developed

Posted: 19 March 2021 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Scientists have developed a model of the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease in rhesus macaques to better test new treatments.

Researchers at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at the University of California, Davis, US, have developed a model of the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease in rhesus macaques. The new macaque model could allow better testing of novel treatments.

According to the researchers, understanding what happens during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease could be key to preventing or reversing symptoms of the condition. However, it is difficult to study therapeutic strategies without an effective animal model that resembles the human condition as closely as possible. Much research has focused on transgenic mice that express a human version of amyloid or tau proteins, but these studies have proven difficult to translate into new treatments.

The team say that humans and monkeys have two forms of the tau protein in their brains, but rodents only have one.

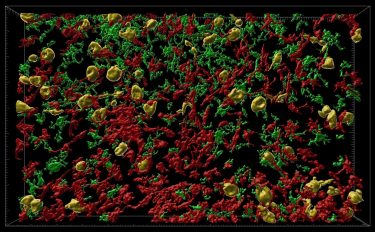

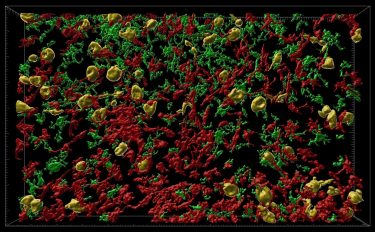

Inflammatory cells (red and green) flood into part of the brain where neurons are affected by misfolded tau protein (orange). This model in rhesus macaque monkeys shows similarities to development of Alzheimer’s disease in humans and could open up ways to test new treatments [credit: Danielle Beckman, UC Davis/CNPRC].

“We think the macaque is a better model, because it expresses the same versions of tau in the brain as humans do,” said Danielle Beckman, postdoctoral researcher at the CNPRC and first author on the paper.

Mice also lack certain areas of neocortex such as prefrontal cortex, a region of the human brain that is highly vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease. Prefrontal cortex is present in rhesus macaques and critically important for cognitive functions in both humans and monkeys. Therefore, there is a critical need for new and better animal models for Alzheimer’s disease that can stand between mouse models and human clinical trials.

The researchers created versions of the human tau gene with mutations that would cause misfolding, wrapped in a virus particle. These vectors were injected into rhesus macaques, in a brain region called the entorhinal cortex, which is highly vulnerable in Alzheimer’s disease.

Within three months, they could see that misfolded tau proteins had spread to other parts of the animal’s brains. They found misfolding both of the introduced human mutant tau protein and of the monkey’s own tau proteins.

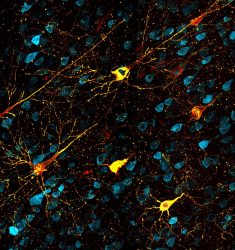

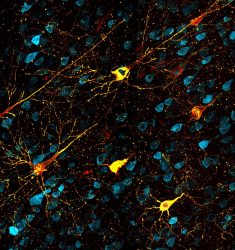

Neurons affected by misfolded tau proteins. Healthy neurons are blue, faulty tau proteins are yellow and protein tangles are red. This model in rhesus macaque monkeys shows similarities to development of Alzheimer’s disease in humans and could open up ways to test new treatments [credit: Danielle Beckman, UC Davis/CNPRC].

“The pattern of spreading demonstrated unequivocally that tau-based pathology followed the precise connections of the entorhinal cortex and that the seeding of pathological tau could pass from one region to the next through synaptic connections,” said Professor John Morrison, lead researcher. “This capacity to spread through brain circuits results in the damage to cortical areas responsible for higher level cognition quite distant from the entorhinal cortex.”

“We think that this represents a more degenerative phase, but before widespread cell death occurs,” said Beckman.

The researchers next plan to test if behavioural changes comparable to human Alzheimer’s disease develop in the rhesus macaque model. If so, it could be used to test therapies that prevent misfolding or inflammation.

The study was published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Related topics

In Vivo, Neurosciences, Protein, Proteomics

Related conditions

Alzheimer's disease (AD)

Related organisations

University of California Davis

Related people

Danielle Beckman, Professor John Morrison